Relational-Cultural Theory Series Previous Articles:

What is Relational-Cultural Theory?

Transforming Community Through Disruptive Empathy

Combining the Neuroscience of Relational-Cultural Theory and Clinical Practice

Relational-Cultural Theory (RCT) in Practice:

The Power of Connection Through Student and Professional Mentorship

By Connie Gunderson, PhD, Jane Larson, MSW, Corrie Ehrbright, MSW, Vanessa Thoennes, MSW, Amy Anderly-Dotson, MSW, Anthony Klar, MSW, Ashley Tuve, MSW, Will Wales, MSW

Relational-Cultural theory (RCT) recognizes the primacy of relationship, and emphasizes the intrinsic human desire for connection through mutual empathy, radical respect, community and social justice. The purpose of this paper is to share the voices and experiences of MSW students who completed an advanced practice course in Relational-Cultural theory at The College of St. Scholastica in Duluth, Minnesota with the instruction of Dr. Connie Gunderson. Core aspects of learning included the opportunity for students to collaborate with faculty at the Jean Baker Miller Training Institute at Wellesley College in Boston, Massachusetts and participate in a mentorship program with RCT practitioners throughout the USA and Canada. Their experiences demonstrate that with the power of connection and the value of intrinsic inter-relationship mutual learning, growth and change are possible as students integrate Relational-Cultural theory into field placements and other professional settings. Connie Gunderson, PhD, LISW may be contacted at cgunderson@css.edu.

This article shares the voices of MSW students who completed a course in Relational-Cultural theory at The College of St. Scholastica. It will briefly describe the course curriculum for your frame of reference and focus on students’ learning and reflections of their professional growth during the course, and the implications of applying RCT in clinical social work practice.

Brief Introduction to Relational-Cultural Theory

Relational-Cultural theory evolved as a developmental and psychological model in the 1970s through the collaboration of four women psychologists, Jean Baker Miller, Irene Stiver, Judith Jordan, and Jan Surrey, in Boston, MA. These women, along with other scholars and practitioners, began to challenge mainstream, traditional psychologies of human development that were grounded in a belief of the separate-self. From their perspectives, psychological theories that valued and fostered a separate-self worldview, based on individualism and autonomy, promoted a culture that was fundamentally antithetical to the health and wellbeing of persons and communities. In refute, the women posited that health, well-being, and growth are based on the primacy and centrality of relationship and relational movement rather than the focus of acting in one’s sole interests (Miller, 1976). This paradigm shift in thought and action has affected how counseling, therapy, organizational development, and policy changes are understood and practiced. In 2012, an editor at the American Psychological Association recognized Relational-Cultural theory as one of the top ten psychological theories of our time (Carlson, 2012). This is a tribute to the scholarship of the women who dared to challenge the status quo in the field of psychology.

Relational-Cultural Theory (RCT):

An MSW Course Curriculum

In the fall of 2014, MSW students at the College of St. Scholastica had the opportunity to study Relational-Cultural theory and its approach to human development, clinical practice, and social justice.

The course curriculum included an in-depth exploration of RCT theory, collaborative mentorship with RCT clinical practitioners, an introductory training experience at the Jean Baker Miller Training Institute at Wellesley College in Boston, MA, and two community-based educational events, hosted by the College of St. Scholastica and the Duluth community, featuring Dr. Judith Jordan and Dr. Connie Gunderson. The course was designed to engage students to learn about growth fostering relationship with each other, RCT mentors, and RCT scholars. The students were encouraged to reflect and practice the tenets of RCT in all aspects of the course. To assist in this process, students worked in small groups with RCT mentors to examine RCT through comprehensive literature reviews and collaborative discussions. Each small group critically reflected on how the theory and tenets applied to clinical social work practice.

A student reflected that RCT mentorship was a unique way to build relationship and foster learning:

I feel very fortunate to have had the opportunity to work with our mentors. They brought a wealth of experience, wisdom, knowledge, and fun to the table. They were willing to answer questions, share resources, and offer guidance. Most importantly, they brought themselves to the relationship and, I believe, we did as well. In true RCT fashion, our mentoring relationship was one of a reciprocal nature with all of us engaged in mutual learning.

This next section includes brief summaries of the students learning and reflections of some of the primary RCT tenets.

Basic Tenets of Relational-Cultural Theory

Mutual Empathy

Mutual empathy is one of the essential factors necessary for growth in relationship (Jordan, 1986). According to Hartling and Miller (2004), mutual empathy is not a static one-way process, nor is it a relational courtesy, but rather a complex skill that helps us “know” another person’s experience. To be empathic requires vulnerability. Jordan (1992) likens mutual empathy to a “life-giving empathic bridge” where people with different views and perspectives can come together and engage in dialogue that creates change (p. 2).

The practice of mutual empathy in therapy encompasses not only empathizing with clients’ experiences but also with their strategies of disconnection (Miller & Stiver, 1994). It is also a corrective experience allowing clients to build positive relational images and know they can have an impact on the world and the people in their lives which, in turn, contributes to a sense of empowerment (Walker, 2004). As clinicians, being mutually empathic also means identifying and empathizing with our own experiences and strategies of disconnection which can interfere with the ability to be fully present and engaged with our clients (Jordan, Walker, & Hartling, 2004).

Walker (2004) notes that all people deserve to be treated with dignity. Radical respect is a key aspect of mutual empathy. Without radical respect it is unlikely that clients would allow themselves to be vulnerable enough to authentically engage in a relationship. The practice of mutual empathy is paramount – without it, healing cannot take place. A student allowed herself to experience mutual empathy as she wrote:

Boston was an opportunity for me to join and experience the special bond the class already seemed to have. I wasn’t sure what to expect. When I walked into the airport the morning we were flying out, ready to cry over the fact I had to leave my babies, two of my classmates greeted me immediately with smiles, hugs, and words of reassurance. It was in that moment that I knew I was going to be part of something special. Special seems like an understatement here. The bond we all created in Boston was nothing short of extraordinary, and that bond continues to grow.

Authenticity

Authenticity is being able to fully represent oneself honestly in relationship (Jordan, 2004). When we are able to be authentic we are able to better know, understand, and discuss our thoughts and feelings with others (Miller & Stiver, 1997). The benefits of authenticity have been stressed in many fields including psychology, sociology, philosophy, and spiritual traditions (Chen, 2004). For example, a recent study on authenticity, life satisfaction, and distress indicated that the ability to be authentic in relationship was connected to an increased feeling of life satisfaction and decreased levels of distress (Boyraz, Waits, & Felix, 2014). As an example of this, a student wrote:

Authentic interpersonal relationships are critical to client health. Yet so many clients come to therapy in a state of profound isolation. RCT is refreshing because the focus is on healthy and authentic relationships, rather than on symptoms of mental illness.

Another student reflected:

The RCT class was like nothing I expected. The class was small and intimate. We got to know each other’s quirks and personalities on a deeper level. This was something new for me, since I was used to blending in, and being unnoticed. In the RCT class I was visible. When I spoke, people heard me, and that was something I had never experienced before. In this environment I learned my voice was accepted. For the first time, I realized I could make a difference outside of the classroom, and connect with others on a deeper level.

These results support the importance of helping clients share their personal stories, explore thoughts and feelings, be true to themselves, and feel free to engage in meaningful ways with others.

Social Justice

As clinicians it is important to understand that chronic exposure to social disparities, such as race, gender, and class-based stereotypes, are painful and foster self-doubt and feelings of unworthiness (Comstock et al., 2008). RCT invites clinicians to think beyond symptom reduction and remedial helping interventions (Comstock et al., 2008). Clinicians are encouraged to explore the social challenges and barriers clients may deal with on a daily basis. For example, Birrell and Freyd (2006) describe in their article, Ethics and Power, how cultural oppression, social exclusion, and other forms of social injustices underlie the pain that individuals in marginalized and devalued groups routinely experience in their lives. During the training in Boston, Dr. Maureen Walker explained that although oppression is often institutionalized at societal levels, it is necessarily enacted in the context of interpersonal relationship, therefore the fragmentation caused by the violation of human bonds can only be healed by new and healing human bonds (Walker, 2014). While at the training in Boston, a student became more aware of an important social justice issue while attending a lecture by author, Allan G. Johnson, who wrote The Gender Knot. The student noticed:

During the training, I was introduced to new perspectives about gender and privilege in our culture. I began to understand how white males have a status of unearned privilege in our society. As a white male with this unearned privilege, I became increasingly aware of how I may be perceived by others based on this unearned privilege alone. For example, I recognized how women are often discounted in our culture by being referred to as “guys.” This demonstrated how “male dominant” our society is.

As a clinical social worker, it is critical to be cognizant of the deep-rooted issues of power and privilege and to be able to address clients’ experiences with their environments and systemic assumptions and practices from a relational human rights perspective.

Boundaries

Many traditional therapeutic models view boundaries as a rigid line of separation. Clients may be subject to what the therapist determines as rules or boundaries. This perspective often carries connotations of control and separateness. From an RCT perspective, boundaries are viewed as an opportunity for connection and a place of meeting and exchange (Walker & Rosen, 2004). One method that fosters a power-with relationship is a conversation initiated by the therapist with a client at the beginning of the relationship. To create an environment that is mutually respectful and safe, therapists and clients need to discuss and clarify the purpose and focus of their therapeutic relationship. Here, boundaries are discussed and mutual agreements are developed to establish a constructive therapeutic relationship. For example, therapists respect clients by focusing on the clients’ needs during the therapy hour, and only use a “judicious use of self” when offering feedback and responses. Clients respect therapists by honoring the therapists’ need for personal privacy inside and outside of the office. This is critical in establishing a positive relational connection (Walker & Rosen, 2004). During the semester, there were discussions about the need for healthy professional boundaries. A student reflected:

I have struggled with the some of the traditional models of mental health treatment. For example, a therapist who is intentionally aloof and objective (if that is even possible) exudes judgment and superiority. Sadly, I have witnessed clinicians who repeatedly tell clients what is wrong with them, interpret clients as manipulative and treatment resistant, and unilaterally design treatment plans that clients must follow or face significant consequences. This does not model a growth fostering relationship, or offer a client a safe place to be vulnerable. An RCT clinician tries to relate with a client in a professional manner with mutual empathy, fluid expertise, a judicious use of self, clear boundaries, and clarity of purpose.

Power

RCT focuses on safe and healthy therapeutic relationships. So the concept of power is central to RCT. Power is present in every relationship. How power is perceived and manifested is critical. RCT suggests that power is defined as the ability to facilitate change (Jordan, 2010). For example, relationships that strive to acknowledge and respect each person’s ability to contribute, while recognizing the different roles and needs each person may have creates an environment that supports empowerment, connection, and growth (Miller & Stiver, 1997). The students explored how they experience power in their work with clients and in their organizations. Recognizing how people use power to interact in relationship has been insightful. One student wrote:

The privilege of going to Boston to learn from the founding scholars of RCT was life changing for me. It’s not every day that someone like me, has the opportunity to meet people like Dr. Jordan, Dr. Banks, and Dr. Walker. They generously supported our efforts, and they invited us into mutually responsive relationships. How amazing to be invited to call or e-mail them with a question, or a thought, and get a response! How amazing to be asked to share our personal experiences, so they could learn from us.

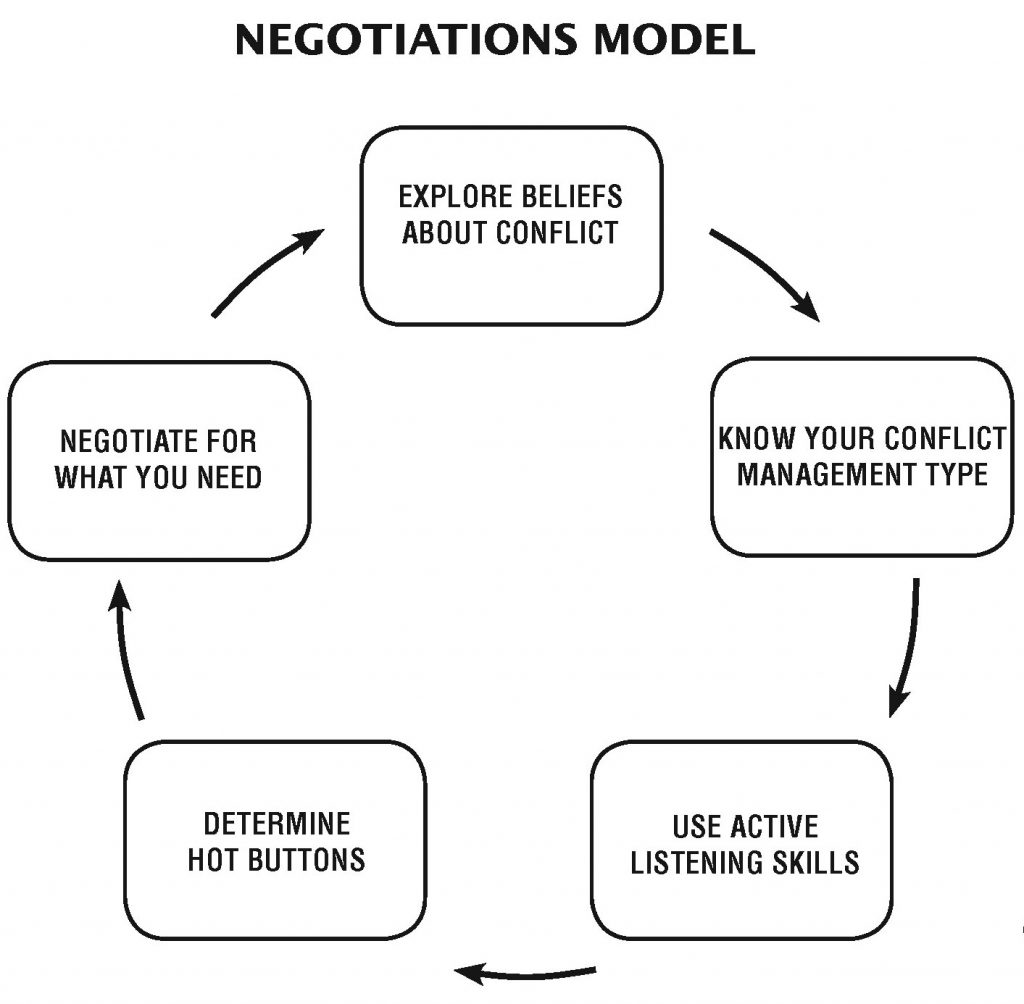

Constructive Conflict

Relationships are not static. They are quite dynamic. In therapy, clients and therapists naturally move along a continuum between connection and disconnection (Comstock et al., 2008). Disconnections and resulting conflicts may cause fear. Conflicts in therapy can be seen as pathways for transforming misunderstandings to empathy, and for building bridges between one another through collective relational struggle (Comstock et al., 2008). RCT suggests that with increased mindfulness and a willingness to address inevitable conflicts that occur in therapy in a constructive “win-win” manner, clients can feel safe, become more attentive and responsive to relational movement, and gain confidence in their ability to grow in relationship. A student reflected on her insights about the importance of providing a safe climate for conflict and struggles to occur:

I have learned so much about the value of relationships and the importance of building them with clients. Many clients have experienced loss and trauma and are searching for safety, so it is important to be able to provide that for them.

RCT has changed my interactions with others – I find myself listening more and asking more questions rather than offering solutions right away, which has always been my instinct. I have learned how to create a space that is open and safe. Through this course I have found my voice and been able to share what I have learned about RCT outside of the classroom.

RCT has also taught me the importance of fostering and maintaining relationships that have already been established, to know when disconnections occur, and how to work through them in respectful ways.

Connection and Disconnection

Therapists will likely work with clients who have been referred by social services, the courts, and other programs. Clients may wish for connection with a therapist and hope that the therapist will care enough to listen and understand their story, and, at the same time, clients may feel ambivalent and guarded about treatment. The desire for connection and authentic engagement may be overshadowed by protective strategies to stay out of relationship and to feel safe – to be relationally disconnected (Jordan, 2005).

A disconnection is defined as a psychological rupture that occurs when a child or adult is prevented from participating in a mutually empathetic and mutually empowering interaction (Miller & Stiver, 1997). According to Miller and Stiver (1997), two key features are necessary to bring about re-connection. A person must be able to take some constructive action within the relationship to make one’s experience known. And the other person in the relationship must be willing and able to empathically respond in a way that supports a new and better connection.

Clients’ disconnections are not the only ones that need to be respectfully responded to. Therapists bring their own strategies of disconnection to a therapeutic relationship. The need for connection, based on mutual empathy, with other professionals is recommended for all who are working in clinical practice. Thus, it is important for therapists to participate in professional supervision to support their own personal and professional growth. One of the fundamental beliefs in RCT is that one never needs to be isolated because of the power of connection. A student wrote about her struggles with connection:

I had a profound life changing experience when I went to the Jean Baker Miller Training Institute. Before leaving for the trip to Boston, my hope tank was on empty. I had been compassionately working for a rural agency. I was devastated when the agency suddenly eliminated my position. When I left for Boston with my cohort, I wanted to isolate. It was what I knew. However, while in Boston, I rediscovered who I was as an individual, a spouse, a mother, and as a social work professional. I realized I had been lost for over two and a half years. My life had been weighed down with shame and guilt. The environment I had been working in created these lonely and negative feelings. I noticed that the most fearful and difficult part of my journey in graduate school has been exploring who I am and who I am becoming. I have had to force myself to look at the positive attributes, skills, and passions that are inside of me.

The Five Good Things

A culture that fosters growth and is grounded in radical respect, hospitality, and community offers an environment that provides us with The Five Good Things: a sense of zest, clarity about ourselves and our relationships, a sense of worth, an enhanced capacity to participate in our world, and a desire for more connection (Jordan, 2010). From this perspective, life’s journey is inherently relational. For example, we grow through and towards relationships during our lifetime, rather than towards separateness and independence (Jordan, 2010). One student expressed her ideas: “We wish to feel safe and to offer safety to others. We wish to give and receive love and kindness. We strive to increase our capacity for relational growth by developing mutual empathy, mutual empowerment, and resilience.” Another student wrote about her experience with The Five Good Things:

Because of this course, I have zest in the face of the most trying time of my life. I have more clarity about myself, others, and my relationships than ever before. I have a sense of worth and an enhanced capacity to be productive. Most of all, for the first time in my life, I have the desire for more connection, and for that I am grateful.

Another student added how RCT concepts are intertwined:

Last year, at the beginning of my RCT journey, Dr. Gunderson spoke about The Five Good Things, growth fostering relationship, mutual empathy, and authenticity. Until then, I had never heard how these concepts could be linked together. I knew instantly, I found a “theoretical home”. Everything, from that point on, has been moving me towards learning how to live and practice RCT in my personal and professional life.

The course taught students to apply theory to real life situations. Students were able to engage with peers, mentors, clinicians, educators, and scholars. They created a safe place to explore, struggle, and support each other to develop personal and professional skills critical for comprehensive clinical practice.

Future Collaborations

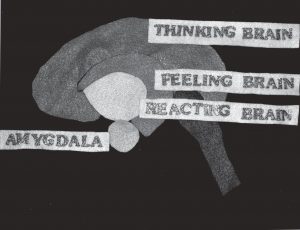

The College of St. Scholastica has integrated RCT into the Masters of Social Work curriculum. There are plans to offer RCT as an undergraduate course to first year students to assist them as they adjust to college life. It is clear, scientific studies are continuing to emerge with data that supports RCT and demonstrates that humans are neurologically wired for connection (Banks & Hirschman, 2014). To assist in providing ongoing evidence in this field of study, Graff, Gunderson, and Larson completed and are in the process of publishing a study on the C.A.R.E. program with MSW students (Graff, Gunderson, & Larson, 2017). This is in the process of being published. This study focused on the relevancy of the C.A.R.E. assessment tool and specific C.A.R.E activities for the relational health of students.

In addition, in collaboration with the Jean Baker Miller Training Institute and Wellesley Centers for Women, engaged CSS faculty and staff, current students and alumni, along with other professionals organized the Transforming Community: The Radical Reality of Relationship Conference in June, 2016. We are currently establishing the cornerstone at the college and with our community to offer ongoing training in Relational-Cultural theory/ therapy in Duluth, MN.

Clearly, the “relational movement” is alive and well on this northern Minnesota campus and in our local community as CSS faculty and students introduce RCT in field placements, professional settings, and with clientele. Collaboration between the College of St. Scholastica and the RCT scholars and practitioners from Boston and elsewhere in the USA and Canada demonstrate that change is possible as we work collaboratively to foster healthier relationships for students, clients, and professionals.

Conclusion

Professional social work education integrates theory and practice and teaches students to engage, assess, and intervene with clients in a wide range of settings. RCT suggests working from a paradigm that places the focus of clinical assessment and intervention on relational development and interaction. From a relational perspective, we approach persons and their environments with a belief in intrinsic inter-relationship. We see the challenges for human rights through a relational lens. We incorporate a relational perspective into how we make policy decisions. For some, this is a significant shift in thought and action.

As the St. Scholastica MSW students graduate and move into the clinical world, integrating the tenets of RCT into their work may not always be easy. A student noted that she has much to learn as she embraces a relational paradigm in her personal and professional life.

I still feel like an infant or a toddler with RCT. I am still in wonder of everything. I am learning and exploring. I realize that RCT is not based on a set of facts to memorize, or quick steps to follow. It is a way of living and being with everyone and everything around me. This theory takes time to develop and understand.

Yet, as more practitioners and organizations truly recognize the centrality of relational interdependency, and as research continues to confirm that we, as humans, are literally hardwired to connect, and as persons consistently challenge power-over systems that intentionally isolate and marginalize “others”, a relational movement that is already underway will be ever-present to foster well-being for all persons and for the planet in which we live.

Acknowledgements

The students of the advanced course in Relational-Cultural theory would like to thank those who offered their assistance while writing this publication. We thank Dr. Gunderson for her endless support throughout the course. Her guidance challenged each of us to explore new ways to connect and relate with others.

We thank our mentors. We are grateful for their willingness to stand with us as we explored the tenets of Relational-Cultural theory. Their experience and insight enhanced our learning and broadened our perspective of social work.

Finally, we thank Dr. Amy Banks, Dr. Judith Jordan, and Dr. Maureen Walker. The training experience was life changing for us. We are moved by your passion for intrinsic human connection and your willingness to support each of us as people and professionals.

References

Banks, A., & Hirschman, L. A. (2015). Four ways to click: Rewire your brain for stronger, more rewarding relationships. New York: Penguin.

Birrell, P.,. & Freyd, J. (2006). Betrayal and trauma: Relational models of harm and healing. Journal of Trauma Practice, 5(1). doi: 10.1300/J189v05n01_04

Boyraz, G., Waits, J.B., & Felix, V.A. (2014). Authenticity, life satisfaction, and distress: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61(3), 498-505. doi: 10.1037/cou0000031

Carlson, J. (2012). In e-Connections Newsletter. Spring, 2012. Wellesley, MA: Jean Baker Miller Training Institute, Wellesley Centers for Women

Chen, X. (2004). Being and authenticity. New York: Rodopi.

Comstock, D., Hammer, J., Strentzsch, J., Cannon, K., Parsons, J., & Salazar, G. (2008). RCT: A framework for bridging relational, multicultural and social justice competencies. Journal of Counseling and Development. 86, 279-287.

Graff, D., Gunderson, C., Larson, J. (2017). [Assessing MSW student’s health and wellness with the C.A.R:E. program]. Unpublished raw data.

Hartling, L. M., & Miller, J. B. (2004). Moving beyond humiliation: A relational reconceptualization of human rights. Excerpts from a paper presented at the Summer Advanced Training Institute: Encouraging an Era of Connection, Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA.

Jordan, J. V. (1986). The meaning of mutuality. Work in Progress, No.23. Wellesley, MA: Stone Center Working Paper Series.

Jordan, J. V. (1992). Relational resilience. Work in Progress, No. 57. Wellesley, MA: Stone Center Working Paper Series.

Jordan, J. V. (2004). Relational resilience. In J. V. Jordan, M. Walker, & L. M. Hartling (Eds.). The complexity of connection: Writings from the Stone Center’s Jean Baker Miller Training Institute. New York: Guilford Press.

Jordan, J. V. (2005). Commitment to connection in a culture of fear. Work in Progress No. 104. Wellesley, MA: Stone Center Publications. doi: 0.1080/02703140802146423 Jordan, J. V. (2010). Relational-Cultural therapy. Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Jordan, J.V., Walker, M., & Hartling, L. M. (Eds.). (2004). The complexity of connection. New York: Guilford Press.

Miller, J.B. (1976). Towards a new psychology of women. Boston: Beacon Press.

Miller, J.B., & Stiver, I.P. (1994). Movement in therapy: Honoring the “strategies of disconnection. Work in Progress, No. 65. Wellesley, MA: Stone Center Working Paper Series.

Miller, J. B., & Stiver, I. P. (1997). The healing connection: How women form relationships in therapy and in life. Boston: Beacon Press Books.

Walker, M., & Rosen, W. B. (2004). How connections heal: Stories from Relational-Cultural therapy. New York: The Guilford Press.

Walker, M. (2004). How relationships heal. In M. Walker & W. Rosen (Eds.). How Connections Heal: Stories from relational-cultural therapy. New York: Guilford Press. Walker, M. (2014). The Power of Connection. Jean Baker Miller Training Institute Lecture. 24. – 26. October 2014. Wellesley, MA: Wellesley College.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Stress Management article and exercises excerpted from

Stress Management article and exercises excerpted from  Prior to teaching in the Undergraduate Social Work Program at The College of St. Scholastica and being Coordinator of that program delivered at Fond du Lac Tribal Community College, Cynthia Donner worked for over two decades with non-profits in the Duluth, Minnesota area. In merging a life-long passion for social justice with the role of educator, she strives to create spaces and opportunities for people to discover the transformative potential of connecting with and contributing to shared stories. Cynthia Renee Donner may be contacted at Cdonner@css.edu.

Prior to teaching in the Undergraduate Social Work Program at The College of St. Scholastica and being Coordinator of that program delivered at Fond du Lac Tribal Community College, Cynthia Donner worked for over two decades with non-profits in the Duluth, Minnesota area. In merging a life-long passion for social justice with the role of educator, she strives to create spaces and opportunities for people to discover the transformative potential of connecting with and contributing to shared stories. Cynthia Renee Donner may be contacted at Cdonner@css.edu. The following material is excerpted from the

The following material is excerpted from the

Reaching adulthood does require a degree of buckling down and getting serious. Let’s face it – there are things we have to do whether we want to or not. But so many of us have lost the sheer capacity for fun, joy, and laughter that even when we have the opportunity, we miss it.

Reaching adulthood does require a degree of buckling down and getting serious. Let’s face it – there are things we have to do whether we want to or not. But so many of us have lost the sheer capacity for fun, joy, and laughter that even when we have the opportunity, we miss it.

Declared by Congress in 1999, May was selected National Military Appreciation Month as a month-long observance honoring the sacrifices of the United States Armed Forces. There are more military related observances during the month of May than any other month, so it is an appropriate time to celebrate the men and women in uniform. During May, we recognize Loyalty Day, VE Day (the end of World War II in Europe on May 8, 1945), Armed Forces Day, Military Spouses Day and Memorial Day.

Declared by Congress in 1999, May was selected National Military Appreciation Month as a month-long observance honoring the sacrifices of the United States Armed Forces. There are more military related observances during the month of May than any other month, so it is an appropriate time to celebrate the men and women in uniform. During May, we recognize Loyalty Day, VE Day (the end of World War II in Europe on May 8, 1945), Armed Forces Day, Military Spouses Day and Memorial Day.

In that spirit we hope the following article, along with the available

In that spirit we hope the following article, along with the available

Excerpted from

Excerpted from