Weaving a Fabric for Transformative Social Justice Learning: Integrating Critical Race and Relational-Cultural Theories

By Cynthia Renee Donner, MSW, LGSW

Critical Race Theory and Relational-Cultural Theory

Critical Race Theory (CRT) emerged in the 1970s in response to changing forms of racial oppression, drawing from earlier movements and philosophers in critical legal studies and radical feminism (Delgado & Stefancic, 2012). Delgado and Stefancic (2012) define CRT as a movement “of activists and scholars interested in studying and transforming the relationship among race, racism, and power” (p. 3). They also state that most social activists agree racism is a common experience, yet difficult to address because of color-blind perceptions of equality that advance white privilege in perceived and real experiences. A prominent base from which CRT evolved is the “social construction thesis” that “holds that race and races are products of social thought and relations” (Delgado & Stefancic, 2012, p. 8).

Relational-Cultural theory (RCT) is a modern psychological theory developed by Jean Baker Miller, and an initial group of scholars—including Judith Jordan, Alexandra Kaplan, Janet Surry, and Irene Stiver through the Stone Center at Wellesley College in Boston (M. Walker, personal communication, March 6, 2017). RCT posits growth-fostering relationships are central to human development (Jordan, 2010). Social justice activists have joined psychotherapists and educators in applying this theory in conjunction with other critical post-modern theories and advances in neuroscience to strategies that promote justice and healing. In particular, RCT examines the oppressive forces and related trauma and social isolation (Jordan, 2010).

CRT is concerned with disparities resulting from forces of structural oppression and was influenced by feminist views on the relationship between power and the social construction of roles and privileges that support patriarchy and domination (Delgado & Stefancic, 2012). These concerns with disparities are also reflected in what Jordan, Frey, Schwartz, and Walker presented on RCT in the June RCT conference that took place at the College of St. Scholastic, Duluth, Minnesota in 2016. CRT examines oppressive social stratification; “it seeks to uncover the mechanism and structures that actually disadvantage people, even those ostensibly designed by institutions to serve the needy” (Ortiz & Jani, 2010, p. 183). Carillo, Hernandez, and Fitch propose that the lived experiences—and understandings of those experiences—leave diverse teachers/learners in a place of “ideological dislocation, in which their interests and passions are neither consistent with Eurocentrically-based curricula nor fit well as acceptable research questions” (Ortiz & Jani, 2010, p. 181). According to Ortiz and Jani (2010), this ideological dislocation is manifest in higher education in in three ways: there is lack of curriculum content that speaks directly to the experiences of students and faculty of color; students frequently lack mentors who can assist them in successfully navigating the learning environment; and having few faculty of color likely affects the overall research agendas of universities. They write: “Racial assumptions become a part of the development of the psyche for members of all groups through internalization, the phase of social construction by which ‘facts’ become a part of the conscious and unconscious” (p. 181).

Jordan (2010) writes that RCT examines the trauma, isolation, and social shame resulting from human disconnection that accompanies forces of oppression. She further poses the basic premise of RCT that justice is served when interpersonal relationships and institutional alignments are grounded in empathy, respect, and mutuality. Both RCT (Walker, 2008) and CRT (Delgado & Stefancic, 2012) consider the role of stories and empathy as significant features of their philosophical dimensions and related practice approaches.

Transforming Community: The Radical Reality of Relationship

The June 2016 RCT conference sparked a unique synergy. People from diverse communities representing many histories of oppression and privilege convened with Jordan and other current leaders in RCT over the three days to listen, share, and reflect. There were heartfelt stories of struggle and transformation, and many individuals reported a renewed strength or clearer vision resulting from the connections made with new people and testimonies during conference sessions and dialogues. It was evident that several presenters and attendees were well steeped in theoretical and/or experiential understanding of oppression and related traumas and disparities from their respective fields of psychotherapy, education, health care, and social activism. But the focus on and practice of RCT over the three days seemed to launch both RCT followers and newcomers into previously uncharted territory rich in meaningful connections that generated substantive qualities of relief, validation, and hope for many in attendance.

Because these kinds of outcomes are not common among professional conferences or circles of learning and action, they merit particular consideration if the desire is to move communities beyond critical analysis to transformative change through shifts in individual and collective consciousness. Through dialogue that adhered to principles of RCT, conference participants demonstrated how the practical application of this theory facilitates growth-fostering relationships among diverse people and deepen engagement among those pursuing transformative change. This has been a significant missing piece in the curriculum and analytical approaches to social justice organizing in the past.

Implications for Social Justice Education

CRT is important to social work education. Like other critical perspectives, it promotes an understanding of racial segregation and the functions of postmodernism that is described by Ortiz and Jani (2010) as a “refusal of positivism, recognition of intersectionality, deconstruction of social constructions, understanding of categorization, and rejection of totalizing categories” (p. 177). In their argument for CRT as a transformational model for teaching diversity, they point out that because race-based ideology is woven into the fabric of the dominant culture, “research methods, theories, and practice techniques taught in social work education rest on the assumptions and values of dominant culture, which, unless subjected to critique, will have questionable applicability to non- Euro-American populations” (p. 182). In a discussion of explicit and implicit curriculum requirements associated with CRT, they further argue that in addition to teaching students about culture they also need to be taught how to “analyze the institutional arrangements of society, assess how they are shaped by dominant cultural assumptions, and recognize how they may disadvantage members of nondominant cultural groups” (p. 189). They conclude by declaring that CRT is a paradigm that calls forth action across all spectrums of social work curriculum with its use of socially conscious indicators, the nature of questions it poses, and the patterns of interaction it promotes can be conceptualized as social work competencies and be concretized into practice behaviors—with some creativity particularly on the part of social work educators.

RCT offers a framework for transformative learning that can be applied across social work curricula (as demonstrated in the June 2016 conference dialogue sessions) to facilitate understanding of CRT in engagement, assessment, planning, and evaluation in a context of growth-fostering relationships. As Ortiz and Jani (2010) assert, “teaching diversity is more complex than trying to attend to the various differences among people in society and the resulting ‘isms’” (p. 190). They further cite the need for students to be prepared to move outside of their prescribed roles and/or comfort zones, and be ready to engage in dialogues that lead to transformative evaluation and outcomes on micro/ mezzo/macro levels. RCT’s foundational principles for cultivating growth-fostering relationships can facilitate integration of CRT learning and development in cognitive, affective, value, and skill dimensions. These principles are grounded in what Jean Baker Miller proposed as Five Good Things which have been described as “Attributes of a growth-fostering relationship: zest, sense of worth, clarity, productivity, and a desire for more connection” (JBTMI, 2017, para. 15). The leading scholars of RCT have contributed research and curriculum in the fields of neuroscience, psychology, social work, education, and social and environmental justice with practice methods that can be integrated into curricular approaches with CRT and other post-modern theories to prepare teachers/learners for the challenges of today’s fragmented world.

At the June conference, Jordan suggested the “social prescription of self-interest” (how we have been socially conditioned to identify with a separate individual self) is a major consideration in examining the isolation that is prevalent among people and in accounting for the increasing disparities along lines of race and class. The separate self that we are conditioned to identify with is constructed along lines of race, class, and gender which creates an isolating fabric of internalized notions of privilege and oppression around our psyche that prevents us from engaging in growth-fostering relationships. Internalizing that isolated separate self is restricting on both cognitive and emotional levels. It requires intentional reflective work to be aware of how these restrictions impact our worldview and relationships. Conscious effort is required to be fully open, empathically present, and responsive with others who are different.

Learning how to connect with others in growth-fostering relationships may be the glue to hold movements together that are focused on transformative justice. People who benefit from or succumb to the dominant individual-centered mindset are not typically invested in transformative social change; and yet they regularly challenge our classroom, professional, and community learning circles. Individuals who expect to be taught what will be on the test, so that they can pass it and receive the degree that will land the desired job are conditioned to do so. The “what’s in it for me” worldview competes with critical thinking to the degree that people adhering to this mindset are not easily motivated beyond personal self-interest to examine the role of structural power and privilege affecting social conditions across micro-mezzo-macro practice fields. The separate individual self-interest orientation combined with privilege that comes with perceived or real socioeconomic status inhibits some people from stepping outside of the comfort zone of conformity and, in the June conference, what Walker called the field of anxiety between right and wrong. CRT suggests that this results from internalized social construction of race and the real socioeconomic benefits afforded people who fit the categorical expectations of white—including behaviors as well as skin colors. Walker further discussed how people are often willing to learn how to talk in politically correct “pseudoempathy” terms (i.e., Minnesota Nice), but not necessarily willing to walk in the field which demands critical curiosity void of judgment and the courage to be vulnerable.

For some the shame of identifying with a privileged group’s discriminatory beliefs or the inability to overcome one or more experiences with oppression is an additional layer of socially prescribed separateness that perpetuates isolation and suppression of voice. As Schwartz and Frey asserted in their presentation at the June conference: “shame is a social emotion,” and too often shaming is a public experience for people in classroom and professional/field encounters. They proposed that learners benefit from a context of mutuality (especially within the dynamics of power in the learning process), and appreciation that their thinking and efforts matter.

The experiences of trauma and shame associated with structural forces of oppression permeate lived experiences of both teachers and learners in a way that influences cognitive understandings of those lived experiences. The socially conditioned orientation toward a separate-self places the challenge of transcending these experiences and related beliefs deep in our individual and collective psyches. Schwartz and Frey went on to state at the conference that we all have “possible selves”— images of who we want/don’t want to be. They suggest that “feedback loops” are a powerful way to learn from and deal with our possible selves and the disconnection in emotional reactions to others’ thoughts and actions—providing the teacher/mentor is grounded in genuine openness to learning and utilizes reflection and support from colleagues.

Jordan cited the importance of relationship in her discussion of relational resilience. She wrote that it is “Movement to a mutually empowering, growth-fostering connection in the face of adverse conditions, traumatic experiences, and alienating sociocultural pressures; the ability to connect, reconnect, and/or resist disconnection. Movement toward empathic mutuality is at the core of relational resilience” (JBTMI, 2017, para. 39).

Implications for Marginalization

Jordan suggested at the June conference that “closed hearts are taught” through socialization of the separate self in a society where “unacknowledged privilege is embedded in every social structure and system of the U.S. culture”. She further stated that capitalism has woven the fabric of U.S. history since early colonization, and stories of injustice continue as the interconnected threads of oppression have tightened under extreme corporate-capitalist control of global economies and political systems. Banks and Craddock pointed out in their presentation at the conference that “social exclusion and perceived social exclusion can be deadly”. They proposed that the psychological resistance to marginalization and other forms of social pain (e.g. overt and covert microaggressions, stereotype threats, exclusionary policies) is a part of the lived experience of people who occupy our classrooms, community, and professional circles. Pain can be enhanced by the combination of ideological dislocation and human disconnection that compels silence while inducing fear and isolation.

How might more inclusive policies and practices transform organizational and institutional systems if they ensured people coming together were grounded in analytical dimensions of RCT and relational dimensions of CRT? Social work values and guiding principles demand that implicit and explicit curriculum ensures inclusion of experiences and perspectives. As teachers, we have more to learn and can be transformed by students. As teacher-learners we must recognize as Frey stated at the conference that “expertise is fluid” and therefore must “be aware of our own disconnection to emotional reactions” to students and others with different in views or experiences.

Walker suggested in her keynote presentation at the June conference that our “embodied difference—or racialized bias/ narrative” is part of the human experience and yet we seldom acknowledge this in ourselves, much less make it part of our classroom discussions, nor hold each other accountable through institutional or community dialogues. Empathic dialogue is increasingly rare in our sociopolitical realms today, with rancorous debate dominating in public discourse and social media. It seems challenging for most people to actively listen to a speaker or connect interpersonally for any length of time, evidenced by the constant need to ask people to turn their communication devices off during class or professional meetings. Dialogue enables us to make meaning of our stories and experiences. Mutual compassion and genuine empathic listening, unconditional positive regard and courageous curiosity are important elements of dialogue that can take us to deeper levels of understanding. The conference dialogue sessions incorporated these elements, and demonstrated the cognitive and emotional levels of understanding that can be reached toward individual and collective transformation.

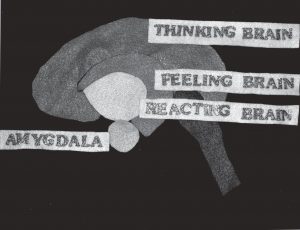

Ortiz and Jani (2010) emphasize CRT principles of asking the right questions, focusing on structural transformation, honoring contextual competence, refusing assumptions. Walker in her conference address identified five practical steps for respectful and courageous engagement with each other: Embrace the whole brain, all voices; pause, breathe; question normalcy; learn about people who’ve resisted racialized power systems; and develop a community of allies. Perhaps more focused and deliberate integration of both these approaches in classroom and community learning circles can foster transformative justice. Given the social and interpersonal isolation in current times, a firm base of knowledge and skills for growth-fostering relationships with diverse people is central to social work education. We are social beings, wired for connection; but unfortunately we are dealing with social systems that challenge this core aspect of humanity. Combined, both theoretical paradigms could help us through the struggles of transformative change—CRT for analysis to help us deconstruct oppressive forces and understand the complexity of intersecting systems, and RCT for building growth-fostering relationships into new and better ways of understanding and being with each other and the world.

About the Author

Prior to teaching in the Undergraduate Social Work Program at The College of St. Scholastica and being Coordinator of that program delivered at Fond du Lac Tribal Community College, Cynthia Donner worked for over two decades with non-profits in the Duluth, Minnesota area. In merging a life-long passion for social justice with the role of educator, she strives to create spaces and opportunities for people to discover the transformative potential of connecting with and contributing to shared stories. Cynthia Renee Donner may be contacted at Cdonner@css.edu.

Prior to teaching in the Undergraduate Social Work Program at The College of St. Scholastica and being Coordinator of that program delivered at Fond du Lac Tribal Community College, Cynthia Donner worked for over two decades with non-profits in the Duluth, Minnesota area. In merging a life-long passion for social justice with the role of educator, she strives to create spaces and opportunities for people to discover the transformative potential of connecting with and contributing to shared stories. Cynthia Renee Donner may be contacted at Cdonner@css.edu.

Relational-Cultural Theory Series, Previous Articles:

What is Relational-Cultural Theory?

Transforming Community Through Disruptive Empathy

Combining the Neuroscience of Relational-Cultural Theory and Clinical Practice

RCT: The Power of Connection Through Student and Professional Mentorship

RCT: It’s All About the Relationship

Unpacking White Privilege: An Experiment in “Going There” with White Relational-Cultural Practitioners

References

Delgado, R. and Stefancic, J. (2012). Critical race theory. New York: New York University.

Ortiz, L. and Jani, J. (2010). Critical race theory: A transformational model for teaching diversity. Journal of Social Work Education, 46 (2). Council on Social Work Education.

Jean Baker Miller Training Institute (2017). Glossary of key terms. Retrieved from: https://www.jbmti.org/Our-Work/glossaryrelational-cultural-therapy

Jordan, J. (2010). Relational-Cultural Therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Torres, C. A. (2007). Paulo Freire, education and transformative social justice learning. Retrieved from http://www.ipfp.pt/cdrom/Pain%E9is%20Dial%F3gicos/Painel%20A%20-%20Sociedade%20 Multicultural/carlosalbertotorres.pdf